If you like your Peak Oil raw, the blogosphere provides plenty of sustenance. At sites such as The Archdruid Report, Casaubon’s Book and The Automatic Earth, we see a small section of society actively preparing for a major discontinuity in the type of lives we lead. One of my favourite representations of this meme is provided at Clusterf**k Nation, a blog run by the author James Howard Kunstler. Kunstler jumps the divide between hard analysis of the perceived problem and fictional representations of how things could unfold. You may not agree with Kunstler, but you will not be bored.

In the non-fiction book The Long Emergency, Kunstler gives an explanation of how the global economy could reverse as oil production peaks. But for me, Kunstler’s fiction leaves a more enduring memory. In the World Made by Hand series we see society shrinking in upon itself. The death of distance lauded in the 1990s has become a cruel joke: the principal means of transport are reduced to foot, horse or boat (bicycles even fall by the wayside through a lack of tires). And political relationships relapse to those existing in the pre-modern period. We are faced with feudalism: medieval free towns, lords of the manor (or their scrap-yard equivalents), serfs, self-contained religious sects and marauding bands of muggers.

At its best, life appears to resemble an Amish country idyll but with a lot more sex. At its worst, the break-down in social order and frequent bouts of extreme violence place us in the pages of Cormac McCarthy’s ‘The Road’.

For the majority of neoclassical economists, such visions are nothing but dystopian fantasies: doomer porn for those with a disposition toward the depressive. Nonetheless, the historical record gives one pause f0r thought: economies do suffer from shocks, which can in turn lead to political dislocations. Within living memory, we saw an economic discontinuity in the 1930s lead to social mayhem throughout Europe and the death of around six million Jews. People still living became unwilling participants in adaptations of Schindler’s Ark and Sophie’s Choice.

So is there any way to get from the existing economic consensus to the type of economic breakdown that Kunstler professes to see?

In my last post, I argued that there was no inherent contradiction between Peak Oil and neoclassical economic thought from a theoretical perspective. The argument was purely over the shape and dynamics of supply and demand curves. To take us into Kunstler’s ‘World Made by Hand’ would require a massive economic contraction sufficient to fracture our global political institutions, in turn setting off a second round of economic deterioration that demolishes our domestic political and social structures. Can Peak Oil take us into the first stage of this process? To do so, a neoclassical economic analysis would be looking for three things: 1) highly inelastic supply and demand curves for oil, both in the short and long term, 2) a supply curve that moves to the left and 3) a key role for oil in economic growth.

Surprisingly, the IMF published a section (entitled “Oil Scarcity, Growth, and Global Imbalances“) within its flagship Word Economic Outlook back in April 2011 that set out some scenarios that indirectly dealt with all these three things.

As regards the elasticity of oil demand to price, the IMF was not the first international organisation to warn of the world’s vulnerability to an oil price shock. In the International Energy Agency’s flagship 2010 World Energy Outlook report, the Executive Summary had a section entitled “Will peak oil be a guest or the spectre at the feast?” which led off with the following paragraph:

The oil price needed to balance oil markets is set to rise, reflecting the growing insensitivity of both demand and supply to price. The growing concentration of oil use in transport and a shift of demand towards subsidised markets are limiting the scope for higher prices to choke off demand through switching to alternative fuels. And constraints on investment mean that higher prices lead to only modest increases in production.

What this statement means is that the oil supply and demand curves are looking highly inelastic. In other words, when the oil price goes up there is not that much room to either substitute out of oil into alternative sources of energy or bring more oil into production.

For the demand elasticity, the IMF went further and applied some numbers to the problem. Over the short term, the IMF sees the demand curve as almost vertical. In their words “a 10 percent increase in oil prices leads to a reduction in oil demand of only 0.2 percent”. This is a pretty frightening statement: it says we have almost no ability to adapt to an oil price shock over the short term. So god help us if a) Iraq plummets into an internecine civil war, b) Israel attacks Iran or c) Nigeria descends into internal chaos. The short-term supply elasticity is also seen as very low at between 1 and 10 percent, and mostly consists of the production buffer held by Saudi Arabia. Should this buffer go, the short-term supply curve becomes in effect vertical (no increase in supply at any price).

Nonetheless, this is not the core of the peak oil doomer scenario; for us to approach collapse, we must see viciously steep long-term supply and demand curves, against which both substitution and technological invention appear ineffectual. And this, in effect, is what the IMF at least suggests on the demand side. It calculates a long-term price elasticity of oil demand (long term defined as a 20-year time horizon) of 7%. This again appears incredibly small. You can double the price but you can hardly make a dent in demand. How could this happen?

For this, we must understand the unique attributes of oil: energy density and transportability. These characteristics are incredibly difficult to replicate. Accordingly, where it has been possible to substitute out of oil, much of the transformation has already taken place. In other words, the shift to gas and coal for electrification previously provided price elasticity for oil, but that has now gone.

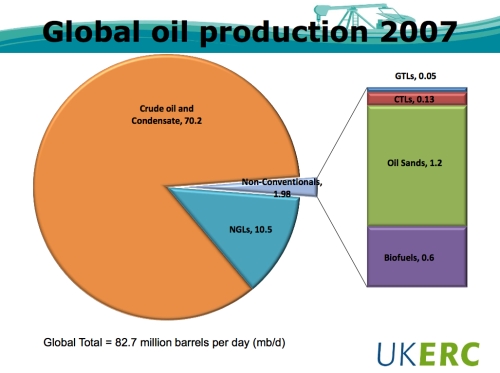

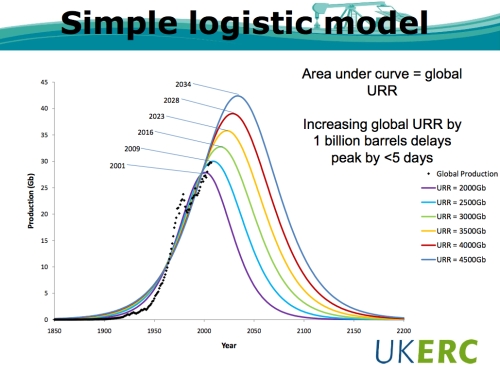

Now the IMF’s baseline scenario for oil production is for 1.5% annual growth. However, in Scenario 2 of the report a contraction in supply of 2% per annum is also considered. The 2% decline number is taken from a paper by Sorrell et al in Energy Policy (that is unfortunately behind a pay wall). In this scenario, we move into a world where the supply curve is moving to the left as opposed to a cornucopian view of the world where technology always pushes the supply curve to the right.

Moreover, if you take this Peak Oil decline scenario and combine it with the IMF’s previously calculated demand and income elasticities, global capitalism suffers a significant shock. In their words:

The most striking aspect of this scenario is, however, that supply reductions of this magnitude would require an increase of more than 200 percent in the oil price on impact and an 800 percent increase over 20 years. Relative price changes of this magnitude would be unprecedented and would likely have nonlinear effects on activity that the model does not adequately capture. Furthermore, the increase in world savings implied by this scenario is so large that several regions could, after the first few years, experience nominal interest rates that approach zero, which could make it difficult to carry out monetary policy.

It should be noted that ‘several regions’ are already experiencing nominal interest rates approaching zero. Thus if we are already entering the foothills of a Peak Oil shock, monetary policy is already incapably of easing the blow over large swathes of the globe including the United States.

Unfortunately, the IMF’s Scenario 3 paints an even bleaker picture since it recognises some of the more recent work on energy’s role in GDP growth. Under traditional approaches, the contribution of oil to economic output has been pegged at around 5% for the tradeables sector and 2% for the non-tradeables based on the cost of oil within the economy. New methodology suggests that these figures could be as high as 25% and 20%, respectively. The argument runs thus: certain technologies are premised on access to energy. Reduce the access to energy and the technology becomes defunct.

As an example, take the first Newcomen steam engine, developed around 1710, that allowed water to be pumped out of coal mines; in so doing, mines were opened up to exploitation at a hitherto unprecedented scale. But the Newcomen engine relied on a bountiful supply of coal. If the coal hadn’t been there, the steam engine could not be operated. The machine technology and the energy can therefore be thought of as a single package: remove one and you cease to have the other.

In a more up-to-date context, think of a sophisticated airline routing algorithm that minimises the number of empty aircraft seats and reduces ticket prices. Doubling the price of jet aircraft fuel not only reduces the number of planes in the air but also reduces the optimisation potential of the algorithm, so setting off second round effects. Oil scarcity can therefore lead to what is, in effect, the disinventing of technology.

Overall, a neoclassical framework built on a slightly more pessimistic premise can have some quite alarming implications. In the words of the IMF:

But if the reductions in oil output were in line with the more pessimistic studies of peak oil proponents or if the contribution of oil to output proved much larger than its cost share, the effects could be dramatic, suggesting a need for urgent policy action.

Nonetheless, even if we pile an oil supply contraction (IMF Scenario 2) on top of a greater role for oil in the economy (IMF Scenario 3), we still are not reduced to the existence of Kunstler’s post apocalypse Amish. The IMF does not give a compound figure for one scenario placed on top of another, but for the US we are probably looking at a 20-25% decline in GDP over a 20 year period against trend and a lot steeper drop for emerging Asia. Assuming trend is for modest growth, this type of oil shock would flat line growth overall.

The relatively benign worst-case outcome of no growth (but no descent), however, assumes that massive price and income shocks can be smoothly absorbed both within and between societies. Unfortunately, we have already seen financial systems struggle with shocks an order of magnitude smaller.

In conclusion, the IMF’s formal neoclassical analysis could easily take us to the brink of Kunstler’s descent, but we would still need something beyond a traditional economic shock to push us over. For that we would need to turn to the science of complex systems or to geopolitics, topics that I intend to return to in future posts.